The Bergen-based company initiated the large-scale registration in NIS 24 June 2019. On this date, four of their ships were registered, and since then, one Wilson ship after the other have started flying the Norwegian flag.

“As a Norwegian company with a head office in Bergen, we clearly prefer to fly the Norwegian flag and have our home port in our hometown”, General Director of Wilson Ship Management, Thorbjørn Dalsøren, says with a smile on his face.

The company, with roots as far back as the 1920s, are proud of both their country and city. There are, however, more reasons why Wilson have chosen to re-register their ships under the Norwegian flag. The relaxing of the NIS regulations, which previously did not allow cargo ships to sail between two Norwegian ports, is one of the reasons why they now can and will choose NIS.

“The world is the market for the shipping industry. We cover most of Europe, including transport between Norwegian ports. And even if we are proud and patriotic when it comes to the Norwegian flag, in our world it is all about equal conditions. It was only when the regulations were amended that we could start flying the Norwegian flag”, says Dalsøren.

Few special requirements

Furthermore, he points out that NIS has few special requirements, and that the ones they do have are so sensible that Wilson are considering applying them to their whole fleet, regardless of flag.

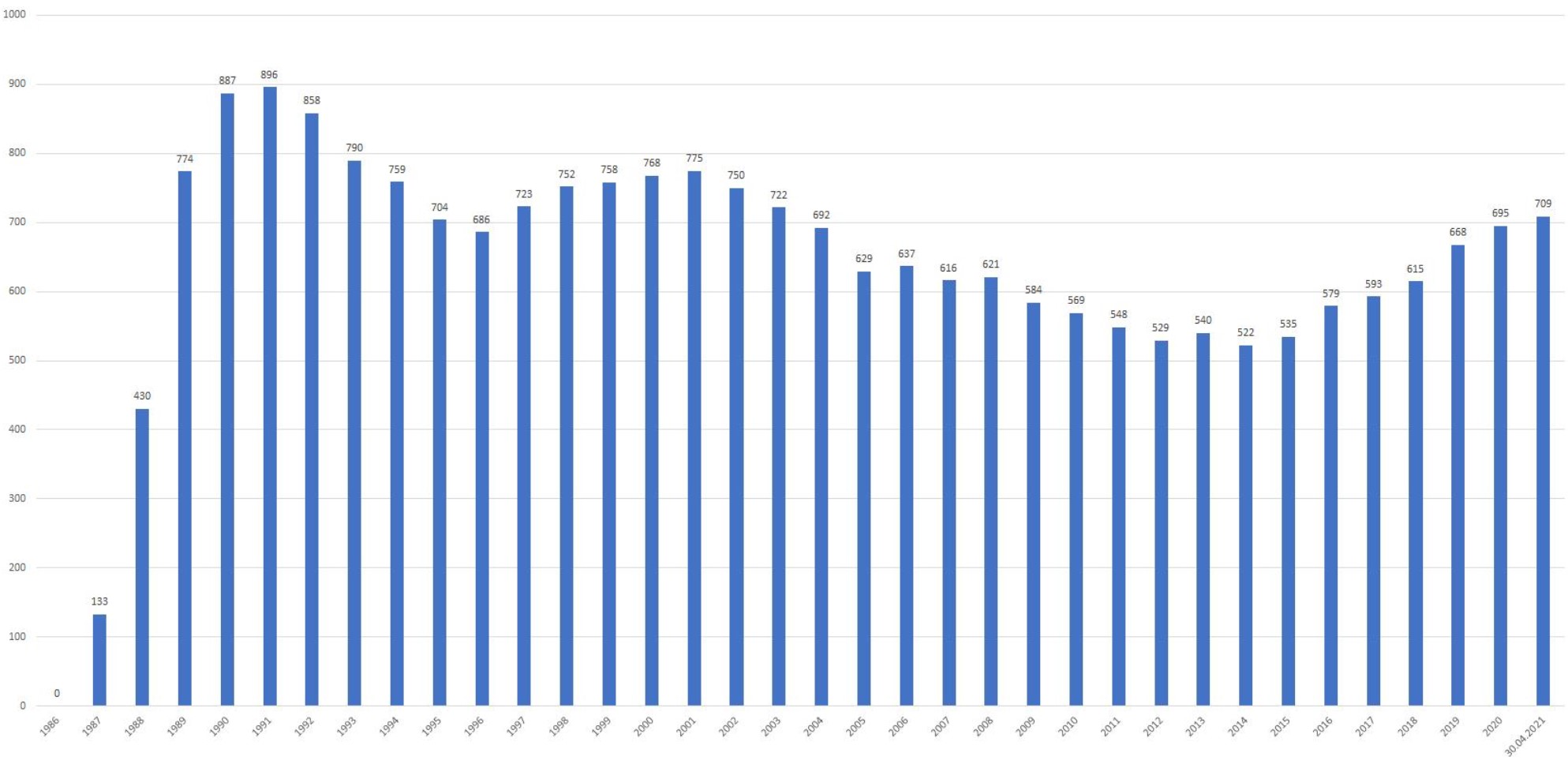

NIS from 1987 - 2021.

“The requirements help improve safety on board. First, they set the standard for maintenance on the ships. Then they choose which flag to fly. They need to choose a flag with conditions that support the selected maintenance standard.

Re-registering during a global pandemic has proved challenging. Still, 18 Wilson ships have started flying the Norwegian flag while countries around the world have closed their borders due to COVID-19. Why?

“In crises such as these we need pragmatic partners. And the Norwegian Maritime Authority is indeed pragmatic. When a regulation or requirement is introduced under the condition that surveyors or others must be able to travel freely and visit ships, we depend on digital solutions to replace these physical visits, and we need these solutions to be fully recognised”, says Dalsøren before adding:

“Wilson makes a port call every 45 minutes, so having a close dialogue with the register is crucial to us. We get that with NIS. Also, the Norwegian Maritime Authority’s slogan is ‘the preferred maritime administration’, and that goes really well with Wilson’s ‘the preferred carrier’, don’t you agree?”, continues Dalsøren.

Head of Department at the Ship Registers, Elisabeth Hvaal-Lingaas, is pleased that NIS continues to be considered an attractive and safe register for shipping companies.

“If the companies had not regarded the register as a good alternative for their ships, the maritime cluster would not look like it does today. We are delighted to see the excellent cooperation and continued growth of the fleet”, says Hvaal-Lingaas.

Sawing off the branch I was sitting on

Lawyer Øystein Meland, at the time a secretary at Bergens Rederiforening, was one of those who worked long days and late nights to establish NIS.

As a shipping lawyer in the eighties most of his working time was spent applying for permissions to register ships abroad.

“One ship after the other flagged out, and then the shipping companies and managements followed. It felt like I was sawing off the branch I was sitting on, and it was only a matter of time until we had to move too”, says Meland.

In the eighties, the shipping crisis hit Norway hard. The price of oil went up from three to twelve dollars a barrel, and the tank transport, in which many Norwegians had invested, went from an annual growth of 17 per cent to a total collapse. Two thirds of all Norwegian shipping companies which were involved in international trade and operating under the Norwegian flag disappeared during that decade. Consequently, the Norwegian fleet shrunk dramatically from close to 30 million gross tonnes to around 10 million gross tonnes in just over a decade.

Running profitable operations with Norwegian seafarers became difficult. Consequently, a large proportion of the Norwegian tonnage was sold to international companies, while a number of Norwegian companies chose to fly another flag and register under a so-called flag of convenience.

Flag of necessity

This kicked off the political battle to establish NIS and a flag of necessity.

“Traditionally a Norwegian ship would have Norwegian owners, hire Norwegian seafarers and fly the Norwegian flag. The problem was that the shipping crisis made it hard to operate with a profit with Norwegian seafarers on board, while Norwegian owners were gradually disappearing. The Norwegian flag disappeared as the authorities liberalised the flag policy and the access to register ships abroad emerged”, says Stig Tenold, Professor of Economic History at the Norwegian School of Economics.

The idea behind NIS is simple: Norwegian ships should be allowed to have foreign crew members on board as long as the ship is not operating between Norwegian ports.

“It took a long time to convince the authorities, the seafarer organisations and the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association. Thankfully, the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association in Bergen took the lead and worked with great dedication to realise NIS”, says Øystein Meland.

In 1985, there was a gradual political acceptance of NIS and subsequently, the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association also changed sides. Finally, the seafarer organisations realised that NIS was the way ahead, and 1 July 1987, in Bergen, the Norwegian International Ship Registered opened their doors for the first time.

The NIS success

As a result, the fleet quickly picked up and went from under two per cent to triple the amount in the world fleet in just a couple of years.

“Undoubtedly, NIS was a success. It saved Norwegian shipping, and the greatest decrease in the number of Norwegian seafarers on international journeys actually took place before the register was established. There was still a need for Norwegian seafarers in Norway”, explains Tenold.

He adds that prior to NIS, Norwegian seafarers became unemployed when the shipping companies flagged out and replaced a Norwegian crew with a foreign crew.

“Without NIS there would hardly be any shipping companies in Norway. Without the companies, the equipment manufacturers would not have a market, the workshops would disappear, consultants, lawyers and subcontractors would not have any assignments – all of the Norwegian maritime industry is built around the shipping companies, and their needs would have been marginalised”, says Meland.

Since he was one of the key persons to open up NIS for registrations, his plan was to register the very first ship in this register. The only problem was that the Knut Magnus Haavik, a lawyer at the Bergen-based shipping company Kristian Jebsen AS, had the same idea. He actually made it into the courthouse before the doors opened.

“I spent the night on the courthouse steps, with biscuits and coffee, to make sure I was the first one”, the lawyer says, laughing. He worked as a legal adviser at the time and was responsible for ship registrations for the company.

He had only been working there for a couple of months when he got the idea to register the first ship in NIS. He recalls, however, that before he could start the preparations, he had to negotiate a collective wage agreement with the national authorities of the at the time communist Yugoslavia. That was anything but easy.

“I had to introduce myself as Dr Professor Haavik just to be able to speak to the right people”, explains Haavik.

He had to write the agreement himself on a borrowed typewriter. When the agreement was finally ready, however, he had all the documents he needed to register the MS Trones in NIS.

Pioneering work

His rival, Øystein Meland, remembers this summer day in 1987 as if it were yesterday.

“Obviously, it became a gimmick to get the first ship registered. My employer, Bergesen, really wanted to be the first. Because of that, I had repeatedly gone through the process with Anita Malmedal, Head of the Ship Registers at the time, to make sure that everything was in order. Well, I managed to get ships number two and three and was very pleased that NIS had finally been established”, he adds, laughing.

“It was pioneering work. The road was made by walking. Those who worked at the ship register back then had learned something very important: to be service-minded and flexible”, says Meland.

He highlights that NIS was the first digital ship register in the world. When they introduced a duty officer phone number, documents could even be processed outside regular office hours.

“Today, NIS is thoroughly developed, digitalised and modernised. We would expect nothing less after more than three decades. Even so, the Norwegian Maritime Authority still has a very enthusiastic and professional team. Innovative and sensitive solutions make the Norwegian flag a competitive service institution”, concludes Meland.